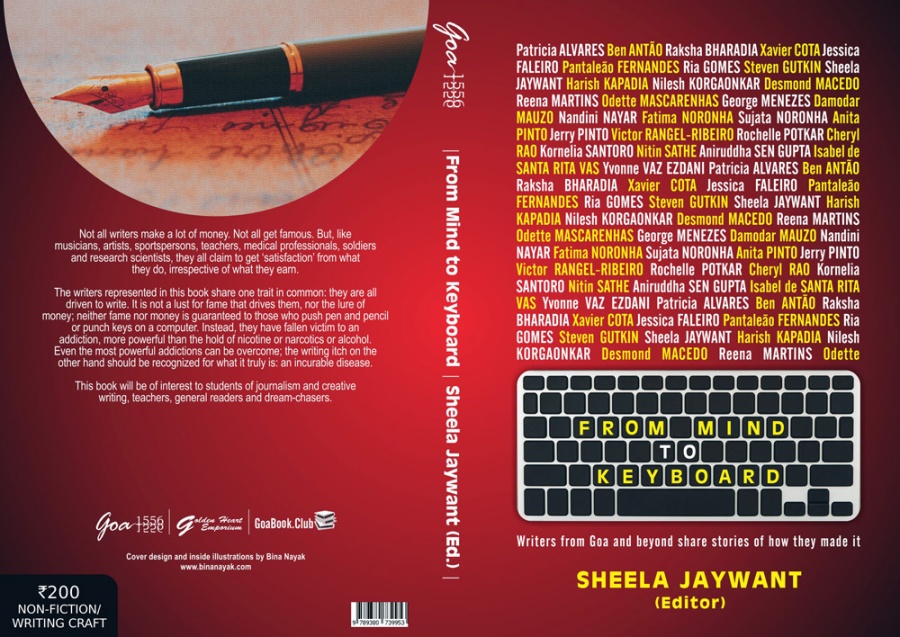

I wrote this piece for a book on writers’ journeys titled ‘From Mind to Keyboard’, edited by Sheela Jaywant and published by Goa, 1556. It seems an appropriate piece to set the ball rolling on this collection of my short writing, as it chronicles the most life-changing decision I ever took. The timing is also right, as it talks of my friend Vijay Nambisan, who played a key role in that decision of mine, and who passed away last week. I don’t intend to carry the full text of my pieces on this blog, just excerpts with links that allow interested readers to download the longer versions, but this first one I have decided to post in its entirety.

The only time in my recollection when I have been seriously depressed over a longish period of time was in the last few months of my stay in college. My four-year BTech course had run its course, and I was done with it for all practical purposes. But I didn’t know what I was going to do next. Almost all my friends had packed up and left for sunnier shores, leaving just a few of us stragglers winding down and wondering what to do with our lives.

I knew I didn’t want to continue with engineering; I knew I wanted to do something connected to writing. But that was all the clarity there was. It was the late 1980s, and work opportunities in offbeat areas weren’t anything like they are today. Let me amend that: work opportunities in offbeat areas were more or less non-existent. So I stayed on in college, ostensibly working on an extension of my final-year project, but in truth casting around rather cluelessly for job options.

I sent some cold enquiries to a few publishing houses, under some misguided apprehension that if I had a job at a publisher’s, I had more of a chance of having my own work published. I never heard back from any of them. I wrote to a few magazines – there were only a very few around, at the time – sending samples of some of my work for college magazines. I never heard back from any of them. The one thing it never struck me to do – when I think back upon it, I am struck by how singularly lacking in initiative I was as a young man – was to use the months that passed to actually write something publishable.

During weekday working hours, I would fitfully pursue my project, which was also stubbornly refusing to show any results. The project that I had chosen to do – or rather that had been thrust upon me by a department sceptical of my ability to handle anything more complex – was the development of a simple mechanism that would use solar energy to power a wind turbine capable of generating electricity. The principles it worked on were very basic – use the sun to heat a metal chimney. The hot air inside would naturally rise towards the opening at the top, while a small clearance all around the base of the chimney would allow air from outside to be sucked in to fill the vacuum created. By narrowing the top as compared to the bottom of the chimney, one could get the rising air to accelerate and exit the top at a high speed. A turbine placed at the top would then spin at a fast rate, and could be used to generate electricity.

My job was to experiment with different geometries for the shape of the chimney and evaluate which one gave the highest efficiencies. It was all so fundamental that there was no way it wouldn’t work. And yet it didn’t. I was constructing brass models about two feet high, and had a pitot tube placed at the openings to measure the wind velocity at exit. But under no circumstances would the damn thing show any readings! (Looking back upon it, with perhaps a little more common sense and a little more knowledge than I had at the time, it seems pretty self-evident that the problem was one of (a) scale and (b) concentration of solar energy; but at the time, my state of mind was such that I didn’t really care whether the contraptions worked or not. Anyway, I had nowhere to go, so stretching the process out didn’t bother me.)

Close to six months went by in this manner. Then, one winter day much like all the others, suddenly my life changed. An old friend called Vijay, two years senior to me and always kind of a mentor, had come visiting. He was a poet – one of two whom I know who would rate among the best at any level – and was working at the time in the editorial department of a city magazine in Delhi. I knew this was my best opportunity, but my shrinking-violet personality (of that time; I have changed much since) prevented me from bringing up the subject while he was there. Questions kept ricocheting inside my head as we spoke of this and that, but somehow they never found their way out of my mouth.

With us during that afternoon was another very close friend, Suheim, who was also in search of his own future, and privy to the confusion of my soul. After Vijay left that afternoon to catch a bus back to Bangalore – where he planned to spend a few days with family before returning to work in Delhi – Suheim asked me, “Why didn’t you tell him about what you want to do? He could have helped you.” I didn’t have anything to say. How do you explain to someone else the foibles of your personality that you don’t yourself understand?

Instead, I trudged off to one more futile inspection of my feckless solar generator, almost crying with frustration at myself. I don’t remember what I did the rest of the day, but I got back to the hostel late in the night. Suheim was sitting on the parapet outside his first-floor room, a couple of doors down from mine.

“Where were you?” he asked.

I must have mumbled something non-committal.

“Vijay was back, you know. He missed his afternoon bus, so he came back to wait for the next one. He just left half an hour ago.”

It seemed an object lesson in how people make their own luck, good or bad.

“He was asking about your plans. I told him about your wanting to write. He said you should send him a letter along with some of your writing, and he will show it to his editor. He’s always been quite impressed with your work on the college mags, and he thinks his editor will almost certainly say yes.”

Suheim had pushed the door open a crack, and I slipped through it with alacrity. The next few weeks saw hectic back-and-forth between Vijay, his editor Probir and me, and by the time the college vacations were ending, I had the assurance of a job as a researcher-reporter. The winter of my discontent had finally given receded and bright possibilities peeked over the horizon.

Into the new semester, I told my faculty counsellor that I was ready to move on. His relief was palpable. I changed my project description from an evaluation of the most efficient geometries of the solar device, to a study of the feasibility of such a device, and got busy putting together my project thesis. At the end of the day, it was a document responding to the question “Would such a device work?” with the answer, “No”, but I put all my writerly skills into stretching that reply to somewhere close to 300 pages.

While I did that, my department faculty prepared for a viva that they wanted to dispatch with minimum fuss. The composition of the board was critical to this. My counsellor, who knew exactly what breed of dog I was, led the strategy. Besides himself, he included on the board our department head (whose idea the solar generator had been, and who was aware of the nitty-gritties of its failure to launch) and the most pliable, unassuming, quiet faculty member he could find. This last gentleman, Professor V, was one who had, some years before, accompanied a rowdy batch of us on what was supposed to be an industrial tour. Its worth was reflected in Goa being one of the stops. During the three-day sojourn, we had spent all of ten minutes at the National Institute of Oceanography, which had absolutely nothing to do with our batch of aeronautical engineers, to justify the trip. After that, the prof left us to our own devices for the rest of the stay. We all loved him!

So, a most amenable board had been composed, but the difficulty was clearly going to be the external examiner. A professor from the Mechanical Engineering department with a special interest in solar energy, he knew nothing of our department’s dynamics, or of the unspoken understanding that the purpose of the viva was purely to slingshot me out of the institute.

As the viva progressed, in fact, I began to realise that he perhaps was not even aware that this was meant to be a final viva. Quite excited about the project itself, he kept asking all kinds of probing questions. Every time he did, I would start with an “Ummm…” as I mentally prepared my response. At that, my counsellor or HoD would quickly step in and respond to his question, deflecting it from its intended target. At other times, the external examiner would suggest other ways in which an element of the project could be approached. I would say “Ummm…” and one of my saviours would step in to explain how that had been tried and had not worked.

After about half an hour of such fancy footwork, my counsellor abruptly hustled the others into signing my thesis to close proceedings. The external examiner did so with a decidedly flabbergasted air, my counsellor and the HoD with visible relief. At the very end, Professor V, who had sat quietly leafing through my thesis during the entire interaction, finally uttered his only words.

“You know, Sen Gupta,” he said placidly. “I’ve been going through your report, and I just have one observation. I think you are a better writer than an engineer.”

I almost laughed with exhilaration at how the whole thing had gone.

“That’s what I’m going to be, sir,” I said happily.

*

POSTSCRIPT: After I started working in Delhi, there were many difficult times – a pitiful salary further decimated by pay cuts, near-bankruptcy, a period when my wife Anjali and I had no money and had to rely on rapidly-dwindling credit card balances even to feed ourselves, and much else – but I’ve never been unhappy again.

Many years later, I took Anjali to Madras to show her around our college campus. Near our department buildings, to my consternation, we chanced upon Professor SK, my counsellor. I didn’t imagine he’d even remember me, but he stopped and got off his cycle when he saw us.

“So, Sen Gupta,” he said, beaming at me. “Did you become a journalist?”

“Yes, sir,” I beamed back.

I introduced him to Anjali and, after a few pleasantries, he pedalled off. Teachers are funny people. You never know when they might sneak in a life lesson or two.

way to go bro or have gone. keep going.

LikeLike

Thanks, Ravi

LikeLike